This event is part of the third chapter for Home Workspace Program 2013-14, led by resident professors Jalal Toufic and Anton Vidokle. For more information on Chapter 3 and the year’s schedule and curriculum, please see HWP 2013-14.

Animism | Curated by Anselm Franke

February 26 to April 3, 2014

Opening: Wednesday, February 26, 2014 at 6pm

Animism has been a multi-part exhibition project realised in various collaborations since 2010. The project interrogates notions of modernity through its 'negative horizon', animism. Originally an anthropological concept denoting humanity’s alleged original beliefs in an animated nature and migrating souls, this project conceives of animism not primarily as belief, but as a category in which modernity and state-reason imagined the absence or transgression of its own conceptual boundaries, chiefly between inanimate matter and non-humans, geared to delineate the status of "person" endowed with a voice and rights. The project does not ask how some people come to perceive objects or nature as "social beings", but inverts the question to delineate how objects are made and the status of person can be withheld or withdrawn. Animism then becomes a lens through which the making of boundaries comes into view, which situates aesthetic processes, such as the effect of animation, against a historical backdrop of modern-colonial mythologies and mobilisations of science. The project seeks to register current shifts from from a critique of alienation, reification and objectification, to a cultural production under the paradigm of subjectivation and the technological mobilization of pre-individual mimesis and relationality. The works and archival documents on display interrogate the symptomatic media-effects of modern boundaries, the nexus between active and passive, poeisis and pathos, and hence recast the ecological network-paradigm of the present in terms of boundary-practices and a critique of media-technologies.

The present edition presents works that interrogate the dialectics of particular formats and genres of the modern institutional imaginary, such as the museum and its relation to time, order and transformation (Jimmie Durham / Chris Marker / Alain Resnais), ethnographic film (Rudolph Poch), the mummy-complex of cinema (Artefakte), animation and the animal-metaphor (Walt Disney, Marcel Broodthaers, Jean Painleve), labor, media and the body (Ken Jacobs), psychiatric boundaries of subjectivity (Angela Melitopoulos and Maurizio Lazzarato), ecstasy (Yayoi Kusama), the continuum of body and technology (Daria Martin), and exemplary "scenes" exploring mediality and the enrollment of mythology and enchantment, materiality and fetishism in the re-configuration of modern power and modern frontiers (Al Clah, Hans Richter, Len Lye,Yervant Gianikian / Angela Ricci Lucchi, Adam Avikainen, Otobong Nkanga), as well as current frontiers in indigenous struggles (Paulo Tavares).

Special thanks to Heidi Ballet, Daphné Praud, Beirut Art Center, Rayyane Tabet, Roy Dib, Cathy Serrano, Jinghan Wang & OCAT, Galerie Marie–Puck Broodthaers, Archives Jean Painlevé, The New Zealand Film Archive, Fundación Augusto y León Ferrari, Hassan Fahs

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 2014

8pm | public

Presentation by Anselm Franke

Modernizing Animism? Specters of Superstition, Partisanship, and Rationalist Control

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2014

The Whole Earth: Antinomies of the Anthropocene

5-7pm | by registration*

In this workshop, we will think through the critique of Cartesian modernity and its binaries, and place this critique within the historical context of the second half of the 20th century, of decolonisation and the rise of ecology and network-capitalism.

Adam Avikainen, CSI:DNR (The Case of Agent BOA’s Antibody Customs), 2014

Most of Avikainen’s paintings, installation works and texts mix autobiographical events with scenarios from science and from fiction. Avikainen’s work delves into the alterity of life in our own bodies and environments, they brings us into imaginative-sensory contact with that familiar strangeness of volcanic, mineral, vegetal and mental realities and dimensions of life. Adam Avikainen is a traveller of margins: not merely of the physical world, but of the territories of language, common imaginaries, of mental geographies, he tests their limits, and at these limits, a world of mimetic inversions and infections begins, a world of anarchic animism, in the face of which Avikainen turns variously into a diviner or a forensic investigator.

The CSI : DNR photograph shows a man with a stethoscope listening to a tree. This photograph was given to Adam Avikainen by his grandfather. The origin of the photograph is unknown, as is the person depicted and its location. According to the artist, the post-catastrophic landscape with the chopped wood looks like Scandinavia or Northern Minnesota. The photograph was used on posters in Bern and Shenzhen to announce the Animism-exhibition, and was lost in New York in 2012.

The second work, a piece of a large painting entitled CSI:DNR Shenzhen that had been executed for the Animism exhibition at OCAT in Shezhen, China, in 2013, did not pass customs in Beirut, where it remains to this moment.

Adam Avikainen sent Ashkal Alwan instructions to execute a work instead. It is incorporating the customs officer at Beirut aiport into the artistic narrative.

Plan B - A type of birth control. The Morning after the CSI-DNR investigation.

Plan A - Stuck in the airtube.

Plan O - 333

Fade.

A man sits behind a desk composed of charcoal. Rather, he leans on it, or it leans on him. They need each other. For He is Agent BOA. The constrictor.

When he inhales the smoke from the smoldering desk, this is when the blurring of the camera’s field of vision occurs...upon inhalation, as opposed to exhalation. (Olympus of Japan makes a grand respiratory camera available on AMAZON for those interested in oxygen malabsorption techniques). For Agent BOA, some of his blood passed into his mother’s stream whilst he was still attached, and she developed antibodies against him, rendering him incapable of complete breath...taking, never giving gas to the plants that were burned and pressed to compose his torso and testicles and tonsils. And as a result, he possesses all the blood types of all the primates on Earth and its rusted fruit satellites warping time, but not space. A woman glides into the chalk room.

She lays three black snowballs on Agent BOA’s bed sheet (stapled to his wonderfully spicy radish-nipples and wrapped around his desk/coal filter/ viscera).

“This is a bribe.”

“This is a power trip.”

“This is me pleading.”

“This is me stalling.”

“This is me leaving.”

“...”

The door closes and the slight wave of sound spit from the creaking hinge cracks a splinter of charcoal from Agent Boa’s left eye and tumbles from his smoked, leather chin.

Black Lights Crash.

Pan to a bowl of ancient fruit illuminated by the dying embers.

A single ant crawls over the fruit, dragging herself drunk on fermented inky-nectar.

Agent BOA reaches out a calcified toe and rubs it against her sticky left breast.

“The antibodies are beginning to attract.”

Curtain. (White Bed Sheet)

Marcel Broodthaers, Caricatures—Grandville, 1968

Caricatures—Grandville is a slide show for which Belgian artist Broodthaers primarily used images from J. J. Grandville’s book “Un Autre Monde” (1844), juxtaposing these images with newspaper photographs of the student revolts of May 1968 in Paris. “Un Autre Monde” is among the most powerful of Grandville’s works: The collective and satiric phantasmagoria here is exhibited formally by blurring the boundaries and upsetting the orderly hierarchies between people, animals, and things. Broodthaers takes Grandville’s images literally, by using Grandville’s “types,” “characters,” “figures,” etc. like “text.” He exposes the fundamental ambivalence in the phantasmagoric objectification achieved by the caricatures by masking humans as animals and thus unmasking human society as “natural.” Broodthaers simultaneously creates a collective dream-image of an epoch and an “uncanny” depiction of the objectification of both nature and human society in the world of modern science and capitalism.

Al Clah, Intrepid Shadows, from the series Navajo Film Themselves, 1966-69

In 1966 the anthropologists Sol Worth and John Adair asked members of the Navajo Nation in Pine Springs, Arizona, to shoot films “which depict their culture and themselves as they see fit.” The result were seven films, and a book by Worth and Adair entitled “Through Navajo Eyes“. In this book, Worth and Adair highlight that the filmic language used by the Navajo filmmakers reflected the unique importance that “motion“ and “eventing“ have in Navajo culture. “Intrepid Shadows“, made by Al Clah, stands out among the films, At the time of the project, Clah was a 19 year old art student at the Institute of American Indian Art at Santa Fe. Anthropologist Margaret Mead described this film as one of the “most beautiful examples of animism on film“. Clah takes his viewers through a landscape in perpetual motion, in which key symbols of Navajo cosmology appear: the spiderweb as an image of the cosmos, and a “Yeibechai“ mask, embodying benevolent supernatural beings. But above all, the film is reflexive: of the anthropologists as intruders, of the meaning of “being on stage“ for them, but also of the role as an artist, who is an outsider and intruder, too. The film begins as the character of the intruder upsets cosmolgical “balance“ by poking at the spiderweb. The destruction of the web sets a process in motion: a metal hoop begins to roll through the landscape, shadows are being separated from things and become longer and longer: a gap has opened within a world. The film then breaks with another Navajo “taboo“: the “Yeibechai“ mask, reserved for specific ritual, appears in the film, wandering through the landscape. The mask is different from usual deptictions of the “Yei”: its vertical ornamentation is reminiscent of a filmstrip. Its eyes are moving. In the end, the hoop comes to standstill, and rejoins its own shadow. In 2011, the films were repaired and returned to the Navajo Nation for public screenings for the first time since 1966.

Walt Disney, “The Skeleton Dance”, from the series Silly Symphonies, 1929

As the first episode of Silly Symphonies, which Walt Disney Studio produced in 1929, “The Skeleton Dance” exemplifies the very laws of the animation genre. By reworking the motif of the danse macabre it celebrates the victory of life over death in a spectacle that is reminiscent of Mexican celebrations on the Day of the Dead. Quite literally the victory of the animated drawing over the static picture is celebrated. The trope of the Ghost Hour invokes the aesthetics of the uncanny and suggests that Disney is commenting on the animistic quality of animation as the return of the repressed. “The Skeleton Dance” is choreographed to the music by Carl Stalling, based on Edvard Grieg’s “March of the Trolls” and Camille Saint-Saëns’s “Danse Macabre,” and each bone is associated with a musical note—a principle perhaps best expressed in the scene where one skeleton uses another as a xylophone. “The Skeleton Dance” articulates a fundamental principle of animation film, namely that many voices must be combined into a single tune within a barebones musical structure. The “enchanting” effect of the genre is rooted in this principle.

Jimmie Durham, The Names of Stones, 2011

Jimmie Durham’s work engages with what he calls “anti-architecture“, which is a programmatic stance against monumentality, the representation of power, and imperial truth-production. Architecture, for Durham, embodies what could be called the “civilizational complex” - the order of knowledge and Western notions of truth and stability -, and he frequently connects this with the birth of “belief”. What Durham deconstructs is the architecture that serves the representation of power, and that finds in stone the ultimate “dead” material in which it can inscribe its mythologies. Stone here becomes the matter which has to carry the image of the self-same and the dreams of purity and eternity, as passive stuff, pure matter that is itself outside of history, and hence has to carry the burden of signifying the great narrative called History with capital H. Durham puts to question, by way of violation, the scientific distinction between the objective and the subjective, thus unleashing the arbitrariness underneath the surface of a reified order that instrumentalizes stones to its ends, as the material believed to embody the criteria of observer-unrelated objectivity of pure matter. One cannot but laugh when looking at this “order of things”, but what looks back at us through laughter is only the degree of “belief” invested in the genre and institution of the museum itself, the museum as part of civilizations’ universal boundary-making machine.

While previous works displayed and produced for the Animism-exhibition - through stones that mimetically resemble non-permanent objects such as fruit - addressed the process of “petrification“ (as opposed to animation) in relation to the museum, the work displayed in the Beirut-Version The Names of Stones (2011) consists of a collection of small stones, arranged in taxonomic manner, but endowed with human forenames. Thus Jimmie Durham performs a mimicry of what primitive animists have been accused of: the subjectification of objects, the projection of human properties , and holds up a mirror to museological “objectivity“ at the same time.

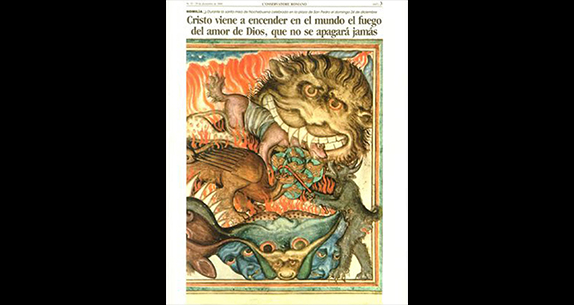

León Ferrari, from the series L’Osservatore Romano, 2001-2007

León Ferrari is a leading figure of the Buenos Aires avant-garde. His works examine ideas and mechanisms that modern culture, with its Christian and Western roots, uses to legitimize its own barbarism. The series of collages “L’Osservatore Romano” (2001–2007) is an example of such a clash. Articles from the Vatican’s daily “Osservatore Romano” that address issues of Christian morality in today’s world, are overlaid with images from the canon of Christian iconography with scenes of the ecclesiastical torture of heretics. These images stem from the Western imagination of evil and damnation, of violence, transformation and metamorphosis. They depict the reality of terror lurking beneath the surface of Western reason and a world that comes into being through terror—from the Inquisition and colonial conquest in the Americas, to military dictatorships of the 20th century,. In the encounter between news reports, history, and art history, the terror of the past resonates in that of the present.

Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi, Diana’s Looking Glass, 1996

The New York-born filmmaker Ken Jacobs is a member of the “New American Cinema” generation of the 1960s and ‘70s who questioned the common film praxes of the time with their aesthetic experiments. Jacobs worked with found picture material, and in allusion to long past viewing and presentation customs, developed a defamiliarized vision of the past. Capitalism: Slavery is based on a stereoscopic image taken in the US of workers on a cotton plantation. The stereograph is digitally animated by switching back and forth between two identical images, while the stroboscopic flickering gradually draws us into the image space. Ken Jacobs plays with the historically determined interaction between matter and spirit, physiology and technology, while simultaneously underscoring the social relations which first made such economies of vision possible. Not least, this work “re-animates” a primal scene of colonial capitalism—slave labor on the plantations.

Yayoi Kusama, Kusama’s Self-Obliteration, 1967

The work of Yayoi Kusama, sculptor, performer, and novelist, remains outside conventional classifications, yet has apparent surrealist, feminist, and psychedelic leanings. There is a distinctively ecstatic quality to her work, a systematic transgression of the boundary between body and environment, between mind and physical space. In the scenographies of her installations and performances, the subject reacts to its appropriation through the relinquishment of its own boundaries, the turning outward of the inward, the collectivisation and spatialization of individuality. “Kusama’s Self-Obliteration,” filmed by eminent experimental filmmaker Jud Yalkut, documents the seminal “nude happenings” performed by Kusama and collaborators during the sixteen years she spent in New York City, when she also organized body-painting festivals, and antiwar demonstrations, and gained significant recognition with her large paintings, soft sculptures, and environmental works. “Kusama’s Self-Obliteration” can be regarded as an exemplary document of Kusama’s practice and its social and political context, a document in which we see her work enacted as an enunciation of collectivity.

Len Lye, Tusalava, 1929

The New Zealand–born painter, sculptor, and filmmaker Len Lye was active in London’s avantgarde scene from 1926 onwards. In his first animated film, Tusalava, he developed a new filmic idiom that synthesized a Primitivist visual language with that of modernist abstraction in the medium of animated film. The work reflects his studies of the indigenous art of Australia, New Zealand, and Samoa. Following Primitivist and Surrealist ideas, he replaced the apparatus of the movie camera with a physical activity aiming at an automatism: drawing. After reading Freud’s “Totem and Taboo,” Lye became an enthusiastic champion of psychoanalysis and especially of the concept of the unconscious, which played a central role in his method of “doodling:” “I doodled to assuage my hunger for some hypnotic image I’d never seen before”.

Chris Marker and Alain Resnais, Les statues meurent aussi (Statues Also Die), 1953

In Les statues meurent aussi, French filmmakers Chris Marker and Alain Resnais trace the colonial appropriation of the African artifact in its two dominant forms: its transformation into an exhibit in an ethnographic museum or into a commercial tourist commodity. The film studies the complex configuration of self-reflection the colonial gaze engenders—the appropriation of the “other” as a (negative) affirmation of the self—insisting on an ontological difference of African artifacts: they are neither “art” nor in and of themselves “spiritual” in a world in which these very categories are without meaning. The film also addresses the problems implicit in the similarity between musealization and the forms of mortification imposed by the medium of film in light of the limitations of the cinematographic “re-animation” it attempts.

Daria Martin, Soft Materials, 2004

Daria Martin’s filmic works, all shot on 16mm, sound out the expressive possibilities of corporeality, of the body in space, exploring what might be called a stylistics of affection. Shot in a laboratory of “embodied artificial intelligence” in Zurich, which focuses on developing the sensory capacity of robotic structures, Soft Materials shows two naked bodies—specially trained dancers—in mutual, bodily exploration with (notably nonanthropomorphic) robotic devices. Based on the experimental work of the laboratory, in which robots “learn” through interaction—which finds its applications, among others, in prostheses and gesture generation—the dancers engage in a choreography of reciprocity and resonance, a two-way exchange between artifice and body. Consequently, the film becomes a scene of interaction between machine and the human sensorium, beyond the technophobic and technophile fantasies which have so decisively shaped popular culture since the advent of technically reproducible media.

Angela Melitopoulos and Maurizio Lazzarato, Assemblages, 2010

Throughout his life, Félix Guattari, philosopher, psychiatrist and activist sought to lay the foundations for a fundamental critique of modernistic concepts. Shortly before his death in 1992, he was convinced that a “temporary, but necessary return” to animism could deconstruct the ontological tradition of modernity which separates subject and object, nature and culture, man and animal, the animate and inanimate, matter and soul, symbol and thing, individual and collective. These dualisms are, according to Guattari, the reason for the majority of the political, ecological, scientific or aesthetic problems of our time. The video installation Assemblages, which in its expanded form incorporates the archive installations Déconnage and Two Maps, follows the path and thinking of Félix Guattari in his four existential territories which were so decisive in shaping his therapeutic and political practice: the asylum in Saint-Alban, the clinic in La Borde and his journeys to Brazil and Japan. Guattari transformed institutional psychiatry with a “politics of experimentation” and turned it into a laboratory for political and theoretical discussions on the production of subjectivity. Assemblages shows archive footage featuring Félix Guattari,excerpts from documentaries and essay films, radio interviews, interviews with friends and colleagues, footage from the La Borde clinic in France, excerpts from films by Fernand Deligny, Renaud Victor, François Pain, together with material shot during his research trip to Brazil. The archive installation Déconnage comprises a series of footage of an interview with the psychiatrist and resistance fighter François Tosquelles, the founder of the first open, institutional psychiatry during the Second World War in the Saint-Alban asylum. Featuring an interview, photos and a notebook from the Japanese photographer.

Otobong Nkanga, Social Consequences II–Projectiles, 2009

As a visual artist and performer, Otobong Nkanga works in a broad spectrum of media such as installation, photography, drawing and sculpture. In her pluridisciplinary approach the individual is constantly confronted with his own fragility. Nkanga puts forward personal autobiographical elements which accentuate and expose the frailty and instability of man in his environment. «Social Consequences II – Projectiles» 2009 reveals concepts behind ideas of labour, domesticity, home, belonging and possession. These drawings have a surreal, yet diagrammatic feeling, clearly illustrating ‹cause and effect› scenarios, using every day symbolic objects.

Jean Painlevé, Les amours de la pieuvre (The Love Life of the Octopus), 1967

Painlevé’s films categorically refute the modern myth that science is demystifying the world. He intended his films to be taken seriously as scientific documentaries and conducted meticulous research. Only their artistic form betrays his surrealist leanings. He strove for a passionate relationship and exchange with his “subjects.” The trigger for “The Love Life of the Octopus,” Painlevé recounted, was early encounters with octopi, during which he recognized their intelligence, impressive memory, and capacity to express emotions. The film introduces us to the “assemblage” of the octopus, its affective web of relations with its environment, exploring form and movement along a porous border between organism and world, thus involving us in a “becoming-animal” of sorts. Painlevé also engages us in the immersive effects of cinema and narration in both a very thoughtful and passionate way.

Paulo Tavares, Against the State, 2012-2014

In 1996, the government of Ecuador signed a contract with the company CGC (Compañía General de Combustibles) for the exploration of Block 23, a giant oil-concession located in central Amazonia that overlaps with 65% of the traditional territory of the Kichwa people of Sarayacu. CGC planned to conduct explosive seismic tests over a grid of more than 200 thousand hectares, opening 650 kilometers of trails in forest zones that are considered sacred and also vital for local food security.

Against the State shows excerpts of the hearing sections of the case “Sarayaku Vs. Ecuador” before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Costa Rica in July 2011. At the centre of the legal debate is the forest itself: a landscape that escapes the geometries of the state; a populated and living territory whose social nature is little understood by law; a “legal subject” whose presence in court calls for an expansion of the arena of human rights beyond the human.

Anselm Franke is a curator and writer based in Berlin, and currently Head of Visual Art and Film at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt. At the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, he co-curated The Whole Earth. California and the Disappearance of the Outside, and After Year Zero (both 2013). In 2012, he curated the Taipei Biennial, Modern Monsters / Death and Life of Fiction. Previously, he co-curated exhibitions such as Animism (since 2010, Antwerp, Bern, Vienna, Berlin, New York, Shenzhen, Seoul); Sergei Eisenstein: The Mexican Drawings (Antwerp, 2009); Mimétisme (Antwerp, 2008); The Soul, or Much Trouble in the Transportation of Souls (Manifesta 7, Italy, 2008); No Matter How Bright the Light, the Crossing Occurs at Night (Berlin / Antwerp 2006/07), and Territories (Berlin, New York, Malmö, Stockholm, Tel Aviv 2003/04). Anselm Franke has published catalogues and publications and contributes to magazines such as ArtReview, e-flux journal and Parkett.